Liner notes:

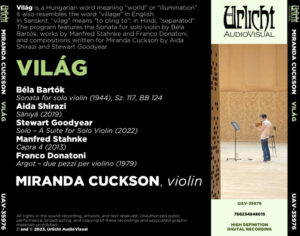

I’m very happy to share my new double-album Világ featuring the Sonata for solo violin by Béla Bartók along with compositions written for me by Aida Shirazi and Stewart Goodyear and works by Manfred Stahnke and Franco Donatoni.

“Világ” is a Hungarian word meaning “world” or “illumination”. It also resembles the word “village” in English. In Sanskrit, “vilag” means “to cling to”; in Hindi, “separated”.

A celebrated artist of the 20th century, Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881-1945) is known for documenting the folk music of Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and other countries of that region, and for his brilliant synthesis of elements of that music in his exquisitely constructed, passionately expressive compositions.

His Sonata for solo violin (1944), composed for Yehudi Menuhin, is one of his last pieces. Dense with notes and technical challenges for the player, it’s been increasingly embraced by violinists and listeners. The four movements evoke essential forms from the Sonatas and Partitas for violin by Johann Sebastian Bach: chaconne, fugue, slow aria (the Largo from Bach’s C major Sonata comes to mind), and fast presto. Like Bach’s pieces, Bartók’s Sonata features inspiring large-scale ambition, athletic virtuosity, and a down-to-earth connection to rambunctious folk dances and catchy rhythms and melodies.

I first learned the Bartók Sonata when I was a college student. Returning to it these days, I’m most struck and delighted by its undulating phrases and by its buoyancy and playfulness on the one hand and melancholy on the other. I enjoy the Tempo di ciaconna’s sweeping sarabande lilt and the lively conversations with the theme amid the intensity of the Fugue. The Melodia, to me, suggests solitude and tranquility, like a lone figure who is getting solace from nature. Then comes the sound of buzzing insects in the Presto (Bartók was an avid collector of bugs), which brings us back to the village and the hearty dancing.

For this recording, I studied the manuscript facsimile and Peter Bartók’s 1994 edition for Boosey&Hawkes, which refers to the manuscript and the composer’s sketches and letters to Menuhin. These sources contain some notes and articulations that differ from the 1947 Menuhin edition. I made choices that felt good to me and I play the original quarter-tones in the Presto.

In my frequent work with composers, I had noticed quite a few drawing upon the music of their native countries – the tunes, native instruments, characteristic rhythms. Thinking about what the many cultures of the world mean to people today, I chose for this album to put the Bartók Sonata next to pieces I had recently commissioned from my friends Aida Shirazi, from Iran, and Stewart Goodyear, from Canada. I decided also to release two works I’ve recently been playing a lot, by Manfred Stahnke and Franco Donatoni. While these don’t draw from the composers’ own ethnic cultures, they develop ideas inspired by folk music and un-formalized language.

Aida Shirazi (b. 1987) emigrated from Iran to complete her college studies in the United States and Europe. She is a co-founder of the Iranian Female Composers Association, a talented group of women who are supporting each other’s artistry and the rights of women. In an interview last year, Aida said “Even when I don’t use anything deliberately or borrow anything [from traditional Iranian music], there is still something with the sonority that people come and say, “Oh, this sounds very Iranian.” I really like it when it’s on a more subconscious level. It leaves something for the audience to hold onto, to interpret, to connect with your music in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily think of. …What happens if you don’t even know who the composer of this piece is, and what would your interpretation be like? It’s that kind of relationship with identity, and how that identity can be liberating or reductive when it comes to the reception and interpretation and appreciation of the work.” She writes about her piece:

Sāniyā is a four-movement work about being taken with a sensual experience as mundane as gazing at the quivering leaves of a tree in the summer breeze and lyricizing it to create a dramatic sonic journey. It is inspired by the game of light and shade, creating forms that appear and disappear all at the same time. The work is the result of my fascination with the sunlight traveling through the leaves and bringing about countless shades of green, impossible to differentiate for the human eye. Sāniyā aspires to capture changes in the white noise of the fluttering leaves in the breeze. Searching for a proper title, I came across the word “sāniyā”, which means the light and shade of the woods in Maazandaraani dialect, which belongs to the people of the Northern Iran. I would like to thank Miranda Cuckson for commissioning this piece. Sāniyā is dedicated to her.

As a concert pianist, Stewart Goodyear (b. 1978) is known for his performances of the classical repertoire such as the complete piano works of Beethoven. As a composer, he has long written and played his own piano pieces, often flavored by music of the Caribbean. His mother is from Trinidad, his father was British. I’m honored that he has branched into writing for violin with this five-movement suite. It dips into both sides of his family background, from the Anglo-Canadian grace of the Waltz to the calypso and steel band in the Dance. He writes about Solo:

My love for the violin began as soon as I was introduced to music, and I actually wanted to be a concert violinist before I became a pianist. Growing up in Toronto, I was surrounded by the different sounds and styles of playing the violin, and adored both the techniques of the fiddler and the violin virtuoso. In Solo, I wanted to create a fusion of both styles in each movement, and therefore create a tour of my childhood with this work. The Waltz and Prelude pay homage to the Canadian folk tradition, the Dance is a fusion of Calypso and toccata writing, and the Chant and Elegy are through-composed, rhapsodic movements. The Elegy closes the suite, and is a very intimate and personal lament for the loss of life due to the COVID pandemic.

German composer Manfred Stahnke (b. 1951) has a keen interest in folk idioms, especially those of non-European countries. Like Hungarian composer György Ligeti and American Ben Johnston, with whom he studied, he has absorbed and been inspired by the rhythmic and harmonic characteristics of various cultures, with the aim of expanding his musical language beyond the Western tradition. His music has a strong basis in microtonal tuning possibilities. Capra 4, from a decades-spanning series of pieces for violin, is a sequence of seven brief interrelated explorations of different jaunty rhythms and tunings. He writes:

The title Capra refers to the physicist Fritjof Capra and his book The Tao of Physics, as well as to the old Latin name for the goat, and via that to the gusla, the Balkan violin, which is covered with a goat skin and very often carries a goat head. In 1987 I started a series of violin solo pieces. The first, Capra 1, was inspired by a Nepalese violinist, a guest at Hamburg Musikhochschule. I was completely fascinated by his playing improvising on fixed speech-like patterns, I suppose. My Capra series is both full of spontaneity and full of “rules” of many musics from all over the world.

Capra 4 (2013) had to wait for a long time to be performed and is now realized in a wonderful manner by Miranda Cuckson. In an additional title it is called Zahlentanz – Dance of numbers, since it runs through the world of the first integers. It starts with just intonated thirds, which use number 5 from the overtone series. Then follows a contemplation of fourths and fifths, numbers 3 and 4. Quite strange is the next movement, based on the numbers 7 and 4. The next uses a scale idea from Indonesia, “Slendro”, where every scale step is close to the overtone proportion 8/7. I combine 8/7 with 3/2, the just fifth. In the next movement, I divide 3/2 into four quasi-equidistant steps. This idea is related to the music of the Tepehua of Mexico, who play a violin imported from Spain long ago. The next movement combines diminished “fourths” 21/16 with augmented “seconds” 8/7 and septimal “sixths” 12/7. The last movement uses overtone and undertone series, a hint to Harry Partch and his “Otonality” and “Utonality”.

Franco Donatoni (1927-2000) was a major Italian artist whose long musical trajectory took place in an era shaped by Bartók and Stravinsky, then by Stockhausen, Boulez, and John Cage. A questioning thinker and the teacher of many well-known composers, Donatoni explored and probed a variety of opposing avenues with his music. He said, “my personal history as a composer is an alternation between ‘separations’ and ‘unifications.’”

.

Argot: two pieces for violin (1979) is from his late period, during which his music had a renewed lightness and he became intrigued by repetition and mutation. “Argot” means a type of language used only among a specific group, or an informal way of speaking (ie, slang) that is not bound by standardized rules. When in use by a people, this kind of language tends to morph and shift, with words developing multiple variations.

The first part of Donatoni’s Argot is more overtly virtuosic, with sections of fast-flowing notes and quick staccato utterances, like chatty, impulsive talking. The second part is also sectional but with more simple fragmented gestures that suggest improvised folk music with intricate ornaments and slides. These are continually altered and toyed with, so that the gestures are both constant and gradually transformed.