Last week, I participated in this conference about the music of Salvatore Sciarrino, at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent, Belgium. Organized by violinist Marco Fusi, the conference was titled “Come vengono prodotti gli incantesimi?” after a piece by Sciarrino. It featured sixteen presenters – devoted and passionate performers of this music and insightful thinkers – most of whom I met there for the first time. I enjoyed how many perspectives on this music were explored and the very interesting and warm exchange of ideas and questions.

My paper/presentation is about violin (stringed-instrument) harmonics in Sciarrino’s music, about the idea of the otherworldly and venturing to the beyond, and his music’s connection to Mendelssohn and Paganini. In 2020 I made videos of the Six Caprices, which I was, and am, very proud of. When I shared them, I wrote very briefly about harmonics and about a Mendelssohnian inspiration. Thanks to Marco Fusi and this conference, I was glad to have this opportunity to talk about my thoughts and approach. I much enjoyed doing some research, rethinking it, and writing my paper, and what I came up with further supported my feeling about this music.

Below is the text of my talk. I also showed these videos and played some short live demonstrations, which I include here as video clips. In the live talk, I actually spontaneously skipped the first several paragraphs and started with “This conference’s title”, but I keep them here for now.

Notes and noises, chance and choices.. Violin harmonics in Sciarrino’s music

The subject of my talk today is, essentially, violin harmonics (or stringed-instrument harmonics) in Salvatore Sciarrino’s music, the interpretation and playing of them, and their relation of pitch and non-pitch, and choice and chance. A couple months ago, when I heard from Marco Fusi that my proposal had been accepted, he asked me to give it a title. I shuffled around some of the elements and words and they eventually coalesced into the title “Notes and noises, chance and choices”. This seemed concise and to the point and it even had a catchy rhyme.

After I sent it in an email, a vague word association kept rattling around in my mind. “Notes and noises, chance and choices”… Something about the rhyme, the rhythm, an unsettling emotion. Then it came to me –

“Double double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and cauldron bubble”

from the Witches’ Chant in Macbeth, the play by William Shakespeare.

In the summer of 2003, I had just finished doctoral classes at Juilliard, I was getting very interested in performing contemporary music, and I had a remarkable experience performing chamber works by Sciarrino at the Lincoln Center Festival with the New Juilliard Ensemble. Sciarrino was present at our concert, and the week prior, the Lincoln Center festival presented his new opera Macbeth, which I attended. Performed by Oper Frankfurt and Ensemble Modern, the extremely quiet two-hour opera featured singers walking on the walls while suspended perpendicularly on wires, and an austere stage-set drawn white-on-black like an architect’s blueprint, with lines receding in exaggerated perspective. The witches hovered singing in a nook upstage, far in the distance. This was all an exciting introduction to the otherworldly art of Sciarrino.

This conference’s title – “How are spells produced?” – concisely addresses the otherworldly qualities of Sciarrino’s music and the practical questions of playing it. Later in this presentation, I will discuss technical questions, demonstrate examples, and look at two works I’ve played, his Six Caprices and the trio Omaggio a Burri. While getting to that, I’d like to discuss connections between Sciarrino’s harmonics and a couple more philosophical threads in his work, which I feel have a bearing on interpreting these compositions. One is the idea of the “otherworldly”- a parallel world or a world beyond. The other is Sciarrino’s dialogues with the music of Mendelssohn and Paganini.

Listeners to Sciarrino’s music often describe it as “ghostly”,“magical”, “spell-binding”, or “mysterious”. Since his early works in the 1960s and 70s, Sciarrino’s work has been very much about perception, our perception of sound and space. Much of his music operates at the edge of audibility, expanding our awareness and heightening our sensitivity to its detailed range of quiet dynamics, its silences, and its breathy, airy, sighing, rustling, and scurrying sounds. This extremely vivid world of sound and silence naturally conjures a feeling of mystery and the unknown, as it provokes startled questions within us as we listen. Where are those sounds coming from? What’s going to happen next? His musical syntax and timing also make his music feel especially unpredictable. The occasional loud outbursts can be shocking.

A frequent gesture in his works is a wave-like phrase that emerges from and returns to “niente” – to nothing. Sciarrino’s philosophy of silence draws us into an alternate, flip-side world. Instead of silences being respites or pauses in a world of sound, in Sciarrino’s world the natural fundamental condition is silence. Sounds then appear out of the silence and make their presence felt, like sea creatures lifting their heads into the air, breaking the surface of the ocean. The ocean of course remains one of the great mysteries of our planet, still vastly unexplored.

Sciarrino has developed new techniques, and explored less common ones, on many instruments. On the violin, one of the devices he has used most is harmonics. Harmonics are a physical phenomenon of high overtone pitches produced by lightly touching a string at one of the nodes that divides the string length in proportion to its fundamental. Whether the fundamental is an open string or a note stopped with a finger, the system of partials functions the same.

In a rehearsal documentary from 2023, Sciarrino said:

“We talk about what we perceive as a limit and that becomes instead the opening of the border. I mean, the boundary is something that opens, not something that closes. What we perceive from the inside as an end, it’s actually the beginning of the earth, the beginning of the world and this is, in my opinion, a very important perspective also for understanding today’s phenomena that otherwise plague us. They are incomprehensible or disturb us because they seem to change the order of the world. No! They are the real order of the world.” [1]

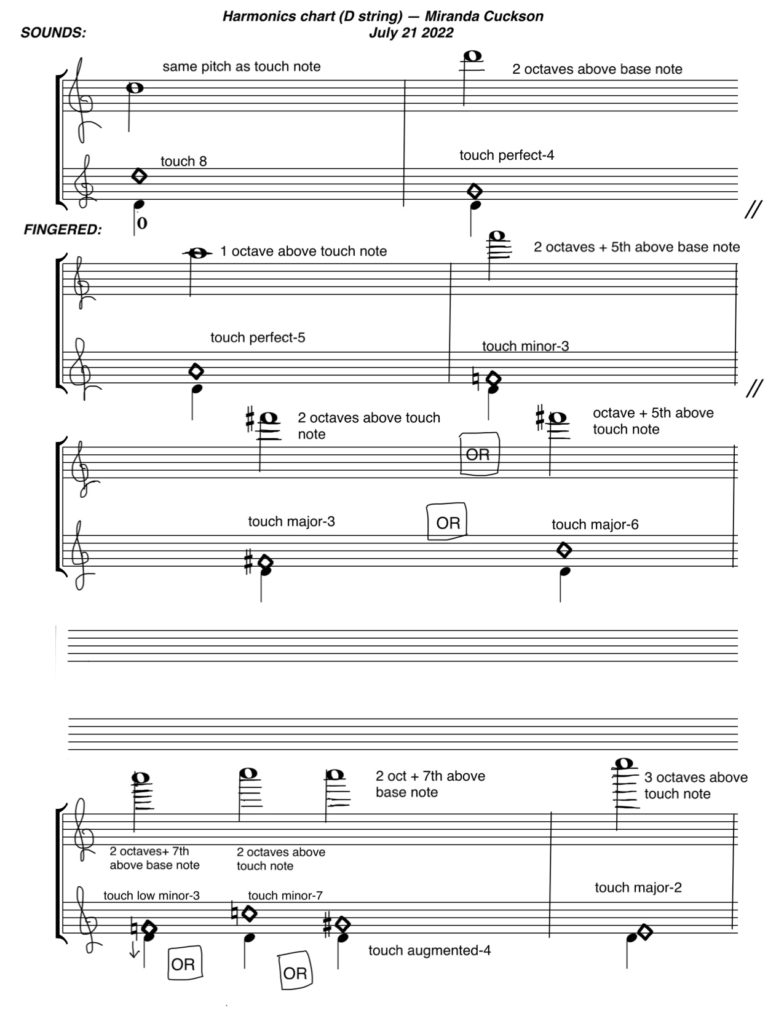

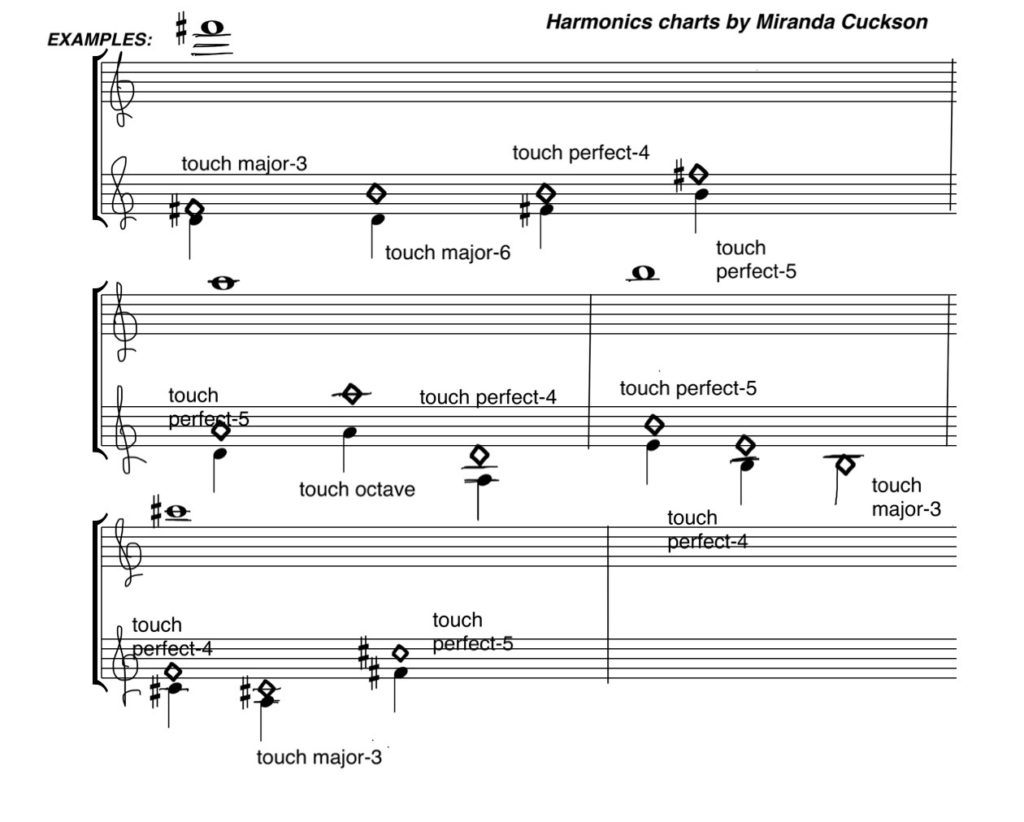

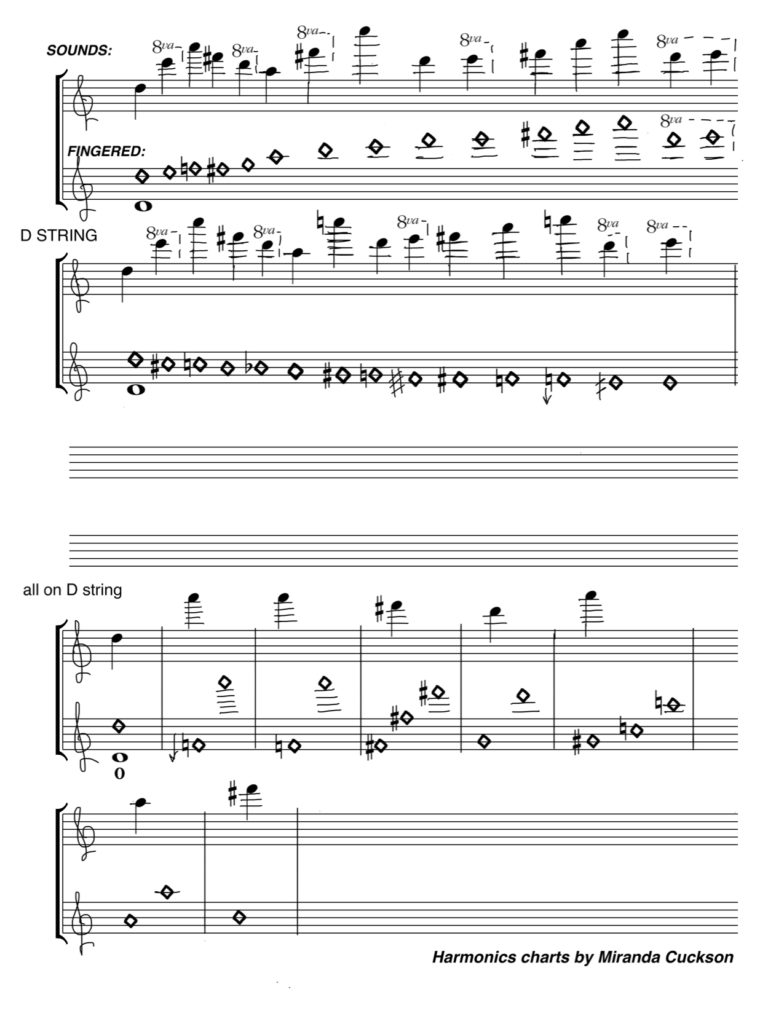

Harmonics are an absolutely integral physical feature of the instrument itself. They are, in essential ways, the “real order” of the violin. However, the full system of harmonics, including practical knowledge of where the nodes are on the string and what pitches they will produce, is not taught in any methodical way by most violin teachers. I believe the reason is that the violin has been traditionally so valued as a cantabile instrument, cherished for its melodic qualities. Young violinists usually encounter a harmonic as a single effect in a piece: a flamboyant flourish at the end of a phrase or a feathery note in a slow passage. Once the player has learned to produce that effect, they’re left to figure out other harmonics on their own. In response to this, a few years ago I made some charts about harmonics, which I posted on my social media and website.

The first page shows harmonics by the interval between fundamental and node (3rd, 4th, 5th harmonics etc), focusing mainly on those most often used and that resonate most easily. The next charts show equivalent harmonic fingerings, and the entire series of partials, including the far less commonly used ones, moving both up and down the string (here the D string).

The harmonics system is the alternative reality of the violin, less known and understood than its usual solid-toned world. Harmonics World is not a world of chaos, it functions according to its own laws and logic, much as there are rules and formulas to the magic and books of spells in many fantasy tales, such as those of Harry Potter, the Lord of the Rings, Narnia, Alice in Wonderland, and so on.

Visually, a page of harmonics even looks like the immaterial spirits of music, with its empty diamond note-heads. Lucia D’Errico writes “memory is explored [in] the cultural memory of sounds..Using traditional instruments.. Sciarrino explores their sonic peripheries.” [2]

Sciarrino calls himself an autodidact and seems to have studied in a very independent way from a young age. Much of what he apparently chose to study was the core classical repertoire: Mozart, Mendelssohn, Beethoven, Brahms. Throughout his music since, there have been many pieces in dialogue with past composers, such as Mozart, Stradella, Gesualdo, and Scarlatti. These can be arrangements, or what he calls “elaborations”, or fragments.

Asked about this, he said: “There are moments of strong hybridization between them. They are not quotations, they are part of me… These people are not figures, they are friends.” [1]

Sciarrino’s Sei Capricci from 1976 were composed for Salvatore Accardo and they reference the 24 Caprices by Niccolo Paganini. Paganini was an awe-inspiring virtuoso, who amazed his audiences to the extent they claimed he had made a pact with the Devil. In choosing Paganini’s Caprices as inspiration, Sciarrino was looking to a model of virtuosity that would feature Accardo, but he was likely attracted also to the sense of the otherworldly about Paganini, the mystery around him and the sense of a different, magical world, of which his playing provided a glimpse.

Paganini was known for the dazzling tricks in his playing, such as left-hand pizzicato, high passagework, and staccato and jeté bowing. It’s significant, though, that harmonics are not an especially frequent effect in Paganini’s music. There are actually no harmonics notated in his 24 Caprices, and not that many in his other compositions. The most substantial instance is the melody played as double-stopped harmonics in the 3rd movement of his first Violin Concerto.

It’s important to remember, along with Paganini’s daredevil image, that he was friends with Rossini and his music came out of the bel canto opera, with the dolce cantabile of its melodies and theatrical rhetoric of the aria. I believe that some of Paganini’s virtuosic techniques truly mimic the operatic singer: the chromatic glissando [chromatic glissando] and the on-the-string slurred staccato have much the same articulated effect as fast coloratura passages.

I’ll talk about each of Sciarrino’s Six Caprices, but to focus on his Caprice No. 1 for a moment: This Caprice opens the set with its most obvious reference – its jeté arpeggios clearly mirror those in Paganini’s Caprice No. 1.

In Sciarrino’s caprice, Paganini’s world is flipped into an alternative state: the solid notes in the Paganini are transformed into harmonics, and the consistent up-down direction of Paganini’s jeté arpeggios turns erratically topsy-turvy, sometimes going up-down and sometimes down-up.

Meanwhile, Sciarrino still throws in a solid note here and there. By doing that, I feel he is maintaining a polarity between the more flesh-and-blood world of the Paganini and the ghostly one of his harmonics, showing that these two planes co-exist. Therefore, I feel it’s important for the performer to differentiate those sounds clearly, and to move between them with naturalness.

This is from a series of videos I made in 2020, of the Six Caprices.

Paganini’s importance as an inspiration to Sciarrino is clear, but I believe the influence of Paganini was also filtered through that of Felix Mendelssohn. Paganini published his Caprices in 1820, when Mendelssohn was 11 years old. Mendelssohn was an extremely prodigious talent. Like Paganini, he himself had a quality of the otherworldly, of the magical and awe-inspiring. But, whereas Paganini’s persona provoked some feelings of danger or suspicion, Mendelssohn’s mainly suggests radiance, naturalness, and a kind of sincere passion.

His Violin Concerto in E minor, written in 1844, has many sparkling moments, but a special passage – famous now but probably very beguiling when first heard – is at the end of the first movement cadenza, when the solo violin plays jeté arpeggios that turn into an accompaniment to the orchestra’s melody. This moment recalls Paganini’s Caprice No. 1.

Mendelssohn’s significance to Sciarrino is evident in another work that he wrote for Accardo, in 1985: the concerto titled Allegoria della Notte. This startling piece toggles between Sciarrino’s music and sections from Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. The fragments from Mendelssohn are altered by Sciarrino but are still very recognizable. At the end of the cadenza, high harmonic arpeggios usher in the return of the orchestra, evoking the parallel moment in the Mendelssohn.

Mainly through the dramatic splicing of the contrasting materials, Sciarrino’s concept of parallel worlds becomes very explicit in this piece. His program note says:

“Imagine listening to Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. Amidst the flashes of consciousness (or the intermittencies of memory) emanates another music, literally generated from the echo of a lyrical impulse. Extending indefinitely, this echo makes perceptible another, parallel space: the uninhabited other side of the Mendelssohn planet.” This is the very beginning of Sciarrino’s concerto, played by Accardo.

I’ve focused on Paganini and Mendelssohn because I feel that the conversation – and shared qualities – among Sciarrino, these past composer “friends”, and his living friend Accardo, form an important context for these pieces. In Sciarrino’s musical echoes of Mendelssohn and Paganini, the sound of resonating notes is a remnant and link to a cultural past, and in his use of harmonics, there is, along with an otherworldliness, a quality of radiance and sweetness, a memory of song and dance and human warmth.

Sciarrino makes use of many types of harmonics. Besides the more common ones, he often uses harmonics on the E string, with the stopped finger on a note that’s already quite high. The resulting pitches are so high, people often aren’t accustomed even to hear them as pitches. [very high harmonics, on C#] He sometimes also has notes fingered extremely high on the string, fingers placed beyond the fingerboard, near the bow in what I call “rosin territory”. [demo beyond fingerboard] The effect is again a sense of traveling to the beyond. These notes reach the edge of physical possibility and start to disappear into the mysterious realm of the inaudible.

Harmonics are affected by the same triumvirate of bowing variables that affect all bowed notes – speed, pressure, and placement on the string. Add accurate left-finger placement to that and you have the necessary factors for good-sounding pitch, factors that have even higher stakes with harmonics. Along with the logical, mathematical system of partials, the flip-side of harmonics is that they are delicate, vulnerable, and especially dependent on factors that can affect the vibration of the string. There is always some element of risk.

This comes into play especially with the harmonics that don’t speak as immediately, like 3rd harmonics, or when harmonics are played in succession at speeds that don’t give time for the partial to be activated. Bow strokes such as jeté or “spazzolare” can add a degree of chance because of how they interact with the string. With his interest in peripheries and thresholds of perception, Sciarrino embraces the elements of chance by using harmonics so prevalently. Chance can be a determining factor at the thresholds in the spectrum of sound from silence to breath to noise to pitch.

Sciarrino’s Caprice No. 2 consists of double-stop harmonics with tremolos, which clearly recall the double-stop tremolos in Paganini’s Caprice No. 6. Paganini’s caprice has one long, sustained melody supported by continuous tremolos on the other string. Paganini Caprice #2

In Sciarrino’s world, the sustained line is fragmented into wave-like phrases, glimmering notes becoming discernible and returning again and again to silence.

The tremolo moves continually from one string to another. A particular technical aspect is the releasing of the lower finger of the tremolo so that it can produce another harmonic, rather than keeping it pressed down like the low note of a trill. This way, Sciarrino is able to involve a greater number of pitches in these gestures. Again I feel that endeavoring to produce the pitches of these harmonics is meaningful, because it connects the piece to a memory of the dolce cantabile, and it also ties together moments of this caprice with a feeling of peaceful return.

Caprice No. 3 involves a bow technique that he calls “spazzolare” or brushing, a diagonal sort of motion across the strings like a car’s windshield wiper. Sciarrino spazzolare

Here the bow stroke introduces a strong aleatoric element and inevitably obfuscates the pitches. If fingered accurately, the harmonic pitches will tend to pop out of the busy texture at unpredictable moments. (I quite like this performance, but I now play this caprice with a wider brushing motion.)

The Paganini corollary isn’t obvious, but it could be his Caprice No. 2 or No. 11. If the wide, vertical string-changing bow movements in the Paganini are turned horizontal, they perhaps become the “spazzolare” wiping of the bow in the Sciarrino. Paganini Caprice #11

Sciarrino’s Caprice No. 4 features a gesture of jeté harmonics in, mostly, sextuplets. These recall the groups of four upbeat 32nd-notes in Paganini’s Caprice No. 9

Paganini Caprice #9

and similarly the last movement of Paganini’s first Violin Concerto.

Paganini Violin Concerto #1 3rd mvt

In those pieces, the groups of four have a strong rhythmic identity and melodic contour. I feel in the Sciarrino, the sextuplets are similarly motivic and should be heard clearly as sextuplets.

In Caprice No. 5, the primary effect is unisons played as harmonics with different fingerings. These produce slight timbral differences, and when alternated quickly, the notes start to merge, rather like when fast-moving blades of a fan blur together. While he calls this caprice “un suspiro” or breath, the effect of the unisons is quite melodic, since there’s time to hear the pitches.

This caprice is similar to Paganini’s No. 12 which has a bariolage bowing across two strings. Paganini Caprice #12

Caprice No. 6 is a compendium of ideas from the previous caprices, and a greater feeling of looseness comes into it. There are longer jeté’s of harmonics that feel more indeterminate and gestural. There are simultaneous harmonic trills on two strings, which are simpler to play than the trills in Caprice No. 2. And a “danzando” middle section is a cheerful Mendelssohnian scherzo in natural harmonics.

Not all compositions in Sciarrino’s large catalogue approach harmonics the same way. Allegoria della Notte and his Piano Trio No. 2 use fewer harmonic overtones and put more emphasis on fingerings in the extreme high register. His recent Sei Nuovi Capricci e un Saluto for violin uses harmonics, but nearly as often, solidly-fingered notes. However, in other pieces, harmonics are modified to bring out more noise than pitch.

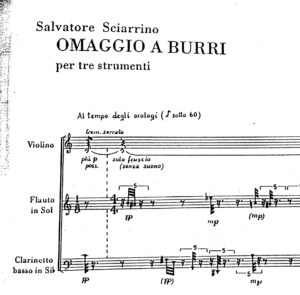

His Omaggio a Burri for flute, clarinet, and violin is a memorial piece to the painter and sculptor Alberto Burri, who died that year, in 1995. Burri was very occupied with physical texture. His artworks explored paint, tar, sand, wood, stone, plastics, metals, and coarse fabrics like jute and burlap. He used fire to make charred surfaces and affixed jutting objects to his paintings.

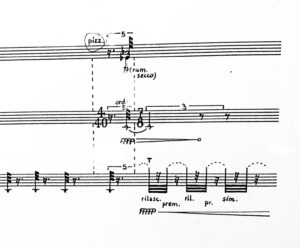

Sciarrino’s interests have also meant investigating the physical surfaces of instruments and the sounds resulting from interaction with their textures. Harmonics are, by definition, played on the surface of the string. At the beginning of Omaggio a Burri, Sciarrino writes for the violin “as soft as possible, only rustling, no sound”. Though notated as a 5th-harmonic on D, the intention is clearly just the friction of hair rubbing against the dampened string.

This friction is similar to the toneless friction of air fluttering across a surface. When the flute erupts with loud multiphonics, the violin joins with harmonics that merge with the flute’s tone. Later, the violin plays a quiet harmonic sigh, marked “flute-like, blown”. Essentially, in this piece Sciarrino uses the surfaces of the violin to turn it into a sort of wind instrument. The violinist even plucks a pizzicato harmonic, marked “dry noise”, to make a dull thud that sounds like a flute tongue-ram.

With his fascination with perception and thresholds, Sciarrino leads us to venture into other worlds, or to listen intently from afar and contemplate what’s over there in the beyond. In that recent documentary, he said:

“Freedom is the ability to choose. In my opinion, there is no freedom if you don’t have the opportunity to choose… If you choose between “this” and “this”, then you are free. I mean, you need to make reality concrete because, in my opinion, freedom is taking one thing and leaving another.”

Sciarrino recognizes that knowing the reality of the world one is in, means knowing that there is another real world somewhere else.

[1] Opoficio Sonoro. “Promenade Sciarrino” April 4, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9W2D-HQ84I

[2] Lucia D’Errico. Powers of Divergence: An Experimental Approach to Music Performance. (Leuven University Press, 2018)