Mario Davidovsky passed away on August 23rd. I was invited to write this reminiscence for New Music Box. Text also below.

[A passionate artist and person, and a fantastic composer, Mario was an imperfect but deeply committed citizen of the world. He was a friend and a mentor to me, much like a loving grandfather. He was supportive and generous, but also sometimes exasperatingly dismissive. I was very fond of him, as I describe below, but I have my own integrity and mind, and many influences and personal associations. I admired many of Mario’s qualities (artistic and human), I learned a lot from him, and agreed with his belief in music’s ability to be emotionally communicative on its own, and that mass saleability isn’t necessarily a measure of artistic worth or excellence. I appreciated the love and support he doled out to me and many people. Some of his compositions, such as the Synchronisms, are well-known classics of 20th to 21st-century concert music.]

I was reading various posts online and absorbing the news that Mario Davidovsky had died, when I received an email asking if I’d like to write a personal reminiscence for NewMusicBox. I was moved and said yes. As I thought about it in the days following, I felt I had pretty much summed up my thoughts on Mario’s music and values in an essay I wrote for celebrations of his 80th birthday. But I appreciate the chance to think more on his personality and my relationship with him, and to add to the wonderful flood of reminiscences, photos and stories about him.

Composing modernist music is an esoteric activity within the general culture, but Mario made substantial connections with a great number of people. He was a passionately involved member of society and the music world. A lot of people have noted his generosity nurturing other artists, his integrity, his vehemently stated opinions, his volubility and notoriously long conversations that would range over world history, science, religion, politics.

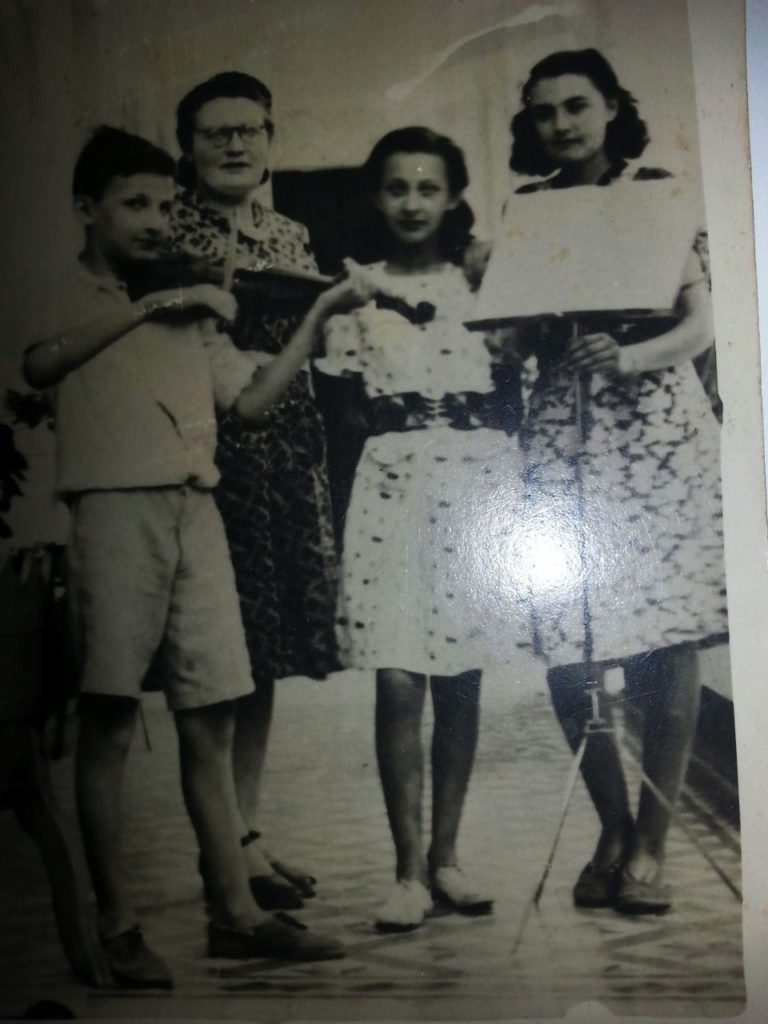

In recent years I would call Mario for no particular reason, just to check in and chat. We talked about music and musicians, of course, but also Silicon Valley, environmental problems, branches of religious philosophy, the big cultural institutions, changing sources of funding. Mario played violin in his youth and that was certainly part of my rapport with him. Another commonality was the Jewish diaspora: both his family and mine (my grandfather) left Europe due to persecution and immigrated to countries in the southern hemisphere (Argentina and Australia respectively). He was always eager to hear about my “peripecias” after I’d been traveling and we’d compare Spain’s characteristics with South America, or the variety of Asian cultures, or one American city’s scene with another. He’d been to many of these places.

By the time I really got to know Mario, he was mainly devoting his time to taking care of his wife Elaine, an elegant former dancer who was ailing for some years and passed away in 2017. He would say, “I hardly go out anymore, I’m at home always” and it was without question where he wanted to be, by Elaine’s side. But he’d also say “Tell me what’s happening! What do you see out there? Have you heard anything good?” I would tell him about interesting concerts going on, and what pieces and programs I was playing. Often he would say “Oh yes, So-and-so was at the Conference in the 1990s” or some other decade, and proceed to describe their music then and whatever he had heard of theirs since, and any news or tidbits of rumors he’d heard about their doings.

He was often warm in his assessment of composers but occasionally he’d say, “Ay, but the music is sheeeet!” About music I was playing that he wasn’t familiar with, he’d ask “What’s it like?” I loved his challenge to express not just its basic characteristics or the inspiration behind it, but to describe from my observation what was happening in the music itself, how its elements seemed to relate.

I first met Mario in 2004 through composer Matthew Greenbaum, who had studied with and known Mario a long time. He invited violist Stephanie Griffin to perform the Davidovsky String Trio on a concert in New York and she asked me to play. I was enthralled with his music from the start. (Stephanie’s group, the Momenta Quartet, was formed from this and I played with the quartet in its first few years. They will perform the String Trio again on October 15 at the Americas Society).

I was very excited about Mario’s pieces and I soon explored and performed more: the Duo Capriccioso, Synchronisms No. 9, three of the four Quartettos, Romancero, the Biblical Songs, Chacona. I got to play all of these for him. As I said in that essay, Mario took many ideas he gleaned from his work with electronics and used them in his acoustic chamber music. In rehearsal he talked about the startling effects of simultaneities and blended sonorities, the singing passages. He emphasized abrupt shifts, saying the effect of switching from non-vibrato to vibrato should be sudden “like you pushed a button,” urging to press down very close to the bridge for noisy attacks marked “coarse!”, then asking for playing at the limits of extreme quiet. Contrasts were not only about dynamics but timbral qualities, from hits and snaps that were hard as stone to gentle, held tones of soft velvet.

For someone known for his work with technology, Mario’s musicality was very linked to older styles of playing. In modern music, glissandos are often played gradually and evenly to draw out the sliding effect, but Mario repeatedly said that his glissandos were a “real portamento,” that is, a quick slide coming at the end of the note, in the style of Fritz Kreisler or Mischa Elman. In a number of Mario’s pieces, such as Duo Capriccioso and the Quartettos, there are spurts of fast spiccato passages or arpeggiated ricochet bowings, and he’d say they should be tossed off “like in Wieniawski, Sarasate.” Sometimes as Mario listened to his music, he would sway his upper body and make expressive gesticulations, as if he were playing along. It makes me think about my former teacher, the violinist Felix Galimir, who was often described as playing like he composed the music himself. To me, Mario composed like he was playing the music himself—the character of his music came so much from the physicality of playing the instruments, even (or especially) when striving for dramatic effects inspired by electronic music.

Mario’s cultural roots were the core of his being, as was his own family. He was immersed in the music community, ready to wade into the thick of things, but if his family needed attention, he would drop everything to be with them. After Elaine passed, he said he was very lonely. There were people calling him, coming by to visit, and he was very appreciative. But he felt sad and alone without his dearest companion and I think was also, in his philosophical Jewish way, dealing with his existential sense of being a solitary soul in the world.

Once when I wrote him something sympathetic, he replied “I never suspected that loneliness could be so overwhelmingly infinite….God must be the utmost lonely thing in the universe—he only has himself…. At least, I have Zabars and can get some cheese and bagels!!!!” It was a joking nudge because we sometimes ran into each other shopping at Zabar’s (indeed often in the cheese section).

I will miss his vast and loving support, his calling me “Querida Miranda” and saying “Heyyyyy!” when he recognized my voice on the phone. I hear the sounds and piquant cadence of his voice all the time now, just as I hear his fierce and tender humanity in his music.